Currying flavour

and a recipe for a Kenyan coconut curry base, Kuku Paka–style

To everyone new here, welcome. I’m Elizabeth, the writer of The Delicious Bits Dispatch, a weekly missive for the curious, blending discovery, reflection, and musings, always wrapped up with a seasonal recipe worth lingering over.

In these early days of the New Year, visions of curry have pushed the sugarplums off stage left in the back of my mind.

Blame it on Lisa McLean and Annada D. Rathi, the architects of a global Curry Night project that these two Substackers cooked up a few months ago.

Curry Night was inspired by Betty Williams and her Piepalooza project, which brought together 36 sweet and savoury recipes and stories for pies of every kind from 36 writers from around the world. Betty gathered them all into one deliciously rich post—a virtual pie potluck that was equal parts comfort and collaboration.

If pie says the holidays and rich indulgence, what might curry signify? In these slowly lengthening days of winter, with mittens and hats, frosty toes, and the desire to hunker down under the nearest blanket—or, depending on your geography, while riding out the tropical rainy season—cooking a fragrant, aromatic curry might just be the best way to spend a Sunday afternoon.

The challenge, of course, is to zero in on just one curry, just one flavour profile, just one country.

Many hands make light work

If there’s a sign that serendipity exists in the world, yesterday it came in the form of Rachel Adjei.

Adjei is the founder of The Abibiman Project, a Toronto-based culinary initiative celebrating the diverse flavours, cultures, and cuisines of Africa and the Black diaspora while supporting food sovereignty and giving all profits to Black food justice causes.

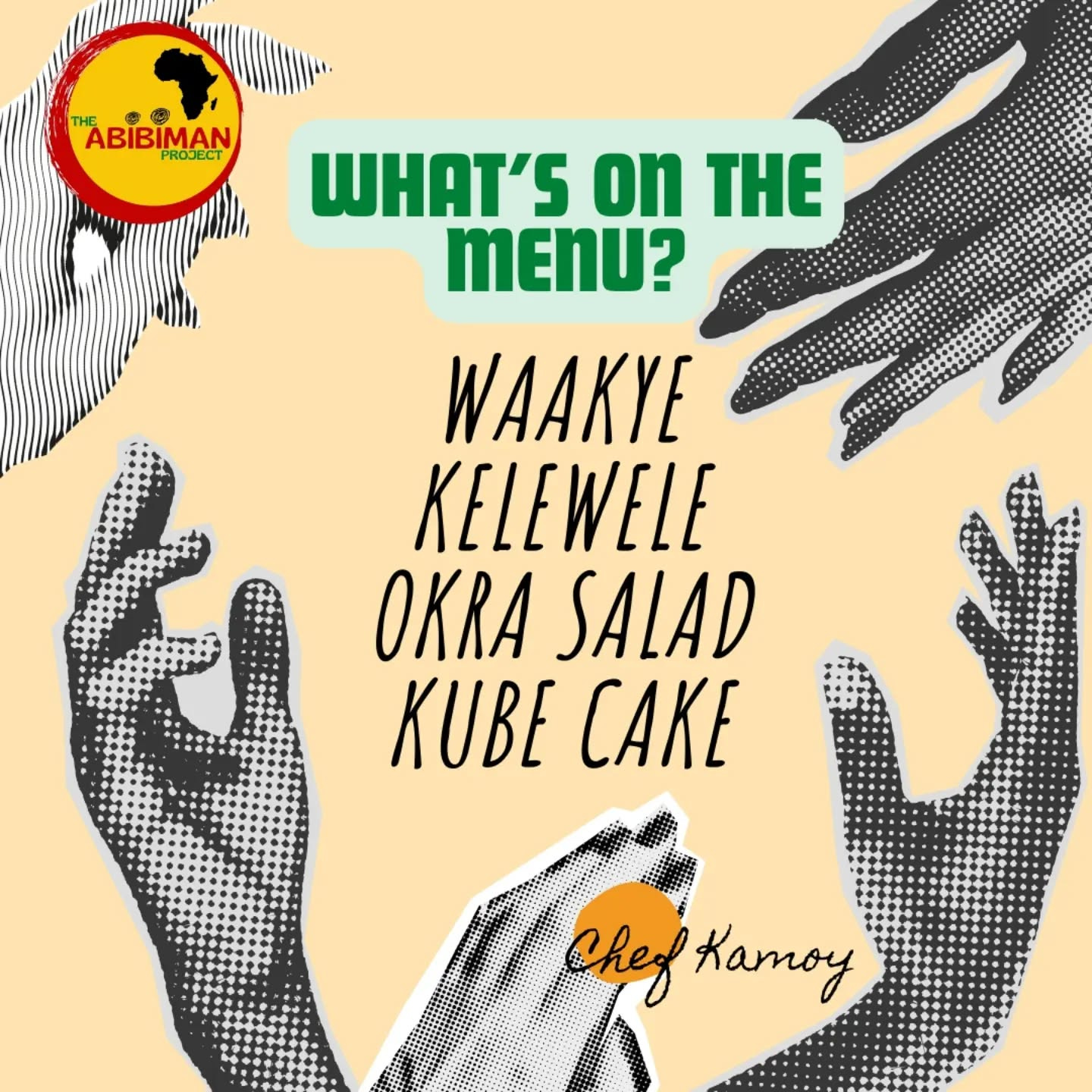

We first met Adjei at one of her Hands Please cooking workshops, an immersive dining experience that had us cooking, and eating, with our hands. The Ghanian dishes were rich in flavour, with a mix of ingredients both familiar and new.

In learning how to make these dishes, the principles that are universal to global curry-making came to the fore: the layering of spices, the slow steps to build the complexity of a dish so that the end result is not a singular note but a choral concert of flavour.

Adjei is a regular at our local farmers’ market, and I take it as no small coincidence that this past Saturday she was there. Selling her unique blend of ready-to-use African spices, pastes and cooking bases, Adjei was also cooking up a vegetarian version of Kuku Paka curry, a Kenyan dish traditionally made with chicken. We could hardly wait to get home to wolf it down…each bite full of the nuance and flavour layering that the best curry style dishes have.

So rather than leaning towards India or Southeast Asia, Africa beckoned and led me into the kitchen. It also got me thinking about the provenance of curry and its place on the global food stage.

What’s in a name?

Long before the word curry entered our collective vocabulary, coming from South Asian and European frameworks, African cuisines were already built around richly spiced, slow-simmered stews and sauces that follow the same cooking techniques. Across the continent, cooks layer aromatics like onion, garlic, and ginger with heat, warmth, and fat, creating savoury dishes meant to be eaten with grains, breads, or starchy sides.1

In West Africa, groundnut stews and palm-oil–based sauces deliver deep, spice-forward flavour, while in the Horn of Africa, aromatic stews built on complex spice blends anchor everyday meals. Along the eastern coast, centuries of Indian Ocean trade further enriched these traditions: places like Zanzibar became culinary crossroads where African ingredients met cloves, cardamom, cinnamon, turmeric and coconut, giving rise to dishes that are unmistakably curry-like in both taste and form.2

African cooking did not borrow the idea of curry—it already held the knowledge: how to coax flavour from spice, time, and care, and how to make a pot of food that nourishes both body and community.

And in the end, isn’t that the essence of what we share and adapt from one another? There has been so much written in recent years about cultural appropriation, about the “true” sources of foods and dishes, and about where a particular technique might have been born.

These conversations matter, particularly when histories have been marginalised or misattributed, but they sit alongside another truth: food has always travelled through hands, kitchens, markets, and migrations, changing as it goes, shaped by encounter as much as by origin. Respecting where food comes from does not require freezing it in place; what survives and thrives is what is cooked, shared, and carried forward.

I like to think of a future in which there is one infinitely long table, where we can break bread together, sharing traditions, ideas, and stories that carry us forward on a wave of delicious discovery that continues to evolve as it is passed along.

If you enjoy these Dispatches—and I hope you do—tap the heart, share, or comment to help new readers find their way here

Kenyan coconut curry base, Kuku Paka–style

adapted from Bon Appétit

about 1 cup, enough for four to six curries

This curry base, inspired by Adjei’s chickpea curry, draws on the flavours of traditional East African coconut curries, where a deeply spiced onion–tomato paste anchors the dish. While Kuku Paka is typically made with chicken, this aromatic base also pairs well with vegetables, legumes or seafood.

You can also order authentic African products from Adjei here.

Ingredients

2 tablespoons neutral oil, such as rapeseed or vegetable

1 tablespoon coconut oil

1 medium onion, finely chopped

3 cloves garlic, minced

1 tablespoon fresh ginger, minced

1 small fresh green chili, finely chopped

1¼ teaspoons ground cumin

1¼ teaspoons ground coriander

¾ teaspoon ground cardamom

¾ teaspoon ground turmeric

¼ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

¾ teaspoon salt, or to taste

1 cup crushed canned tomatoes

2 tablespoons fresh lime juice

In a medium nonstick skillet, heat the neutral oil and coconut oil together over medium heat. Add the onion and cook for 8–10 minutes, stirring occasionally, until soft and lightly golden. Do not brown.

Add the garlic, ginger and green chili and cook for about 1 minute, until fragrant.

Stir in the cumin, coriander, cardamom, turmeric, black pepper and salt, and cook for about 30 seconds to bloom the spices.

Add the tomatoes and cook, stirring regularly, until the mixture becomes until thick and jammy and is no longer watery, about 8–12 minutes. Stir in the lime juice and remove from the heat.

Cool and transfer to an airtight container and refrigerate for up to 7 days or freeze in tablespoon portions up to 3 months

Gbegbe, B., & Forde, L. The African Kitchen. Interlink Books.

“The History of Groundnut Stew.” Ghanammafufu & Vegan, gwafuvegan.com.

“The Spice Legacy of East Africa: A Cultural & Culinary Tour.” Silverback Africa, silverbackafrica.com.

UNESCO. Indian Ocean Trade Routes (Cultural Exchange and Foodways).

Elizabeth, what a beautiful and thoughtful piece made from equal parts history, reflection, and sensory invitation. I loved how you wove together the cultural depth of curry-making with personal moments of discovery. Your spotlight on Rachel Adjei and The Abibiman Project was especially moving; it reminded me how food can be both resistance and joy. And the way you reframed curry not as something borrowed, but something deeply rooted across cultures, was both necessary and powerful. Thank you for drawing that long table so vividly.

This was so stunning, Elizabeth. Thank you for sharing . I have chills and goosebumps . Really really hit home. Grateful for your share