What lies beneath

and a recipe for briny sardine rillettes

To everyone new here, welcome. I’m Elizabeth, the writer of The Delicious Bits Dispatch, a weekly missive for the curious, blending discovery, reflection, and musings, always wrapped up with a seasonal recipe worth lingering over.

I’ve only ever seen whales in the wild twice before.

Once was in Mexico, where the heat and sand and tropical air felt somehow jarring against the smooth, sleek bodies rising in and out of the water, even though I knew they had come to this sheltered corner of the Pacific to give birth. In my mind, whales belonged to deeper places: cold, dark water, mystical creatures surfacing briefly from icy depths to offer we humans a glimpse of their mystery.

It wasn’t until 2022, in Quebec, that I saw humpback whales in what felt like their truest element—the crystalline, cold of the St. Lawrence River estuary, where river meets ocean.

In this pocket of the province, wild beauty reveals itself in many forms: the drama of cliffs, tides, protected landscapes and raw coastline; food rooted in cold-water seafood, local farms and foraging; small, human-scaled villages; and a sense of slowness, restraint, and authenticity.

When we’re in a new destination, there is nothing we love better than to start driving, end point unknown, with no itinerary in mind. And as is my our wont, any wayward signpost is a signal to stop—who knows what hidden treasures await at that farmstand, dairy, art gallery?

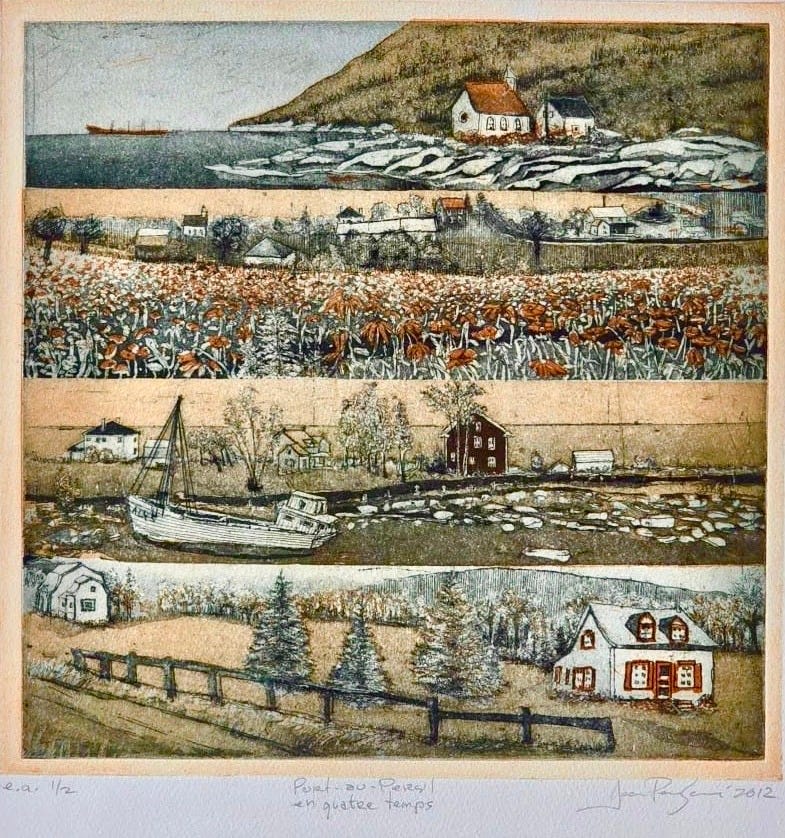

So it was we found Jean-Pierre Sauvé’s atelier, tucked away from the road, and barely announced with a modest sign.

And that’s when I first fell in love with a graveur.

Prints are often misunderstood as secondary works, when in fact they are among the most deliberate and technically demanding forms of artistic expression. Commercial prints—the staple design item for everything from hotel rooms and corporate offices to home décor—can help fill a design void, add life, and express personality. But they differ fundamentally to the prints of an artist such as Sauvé, especially when created through an intaglio method; handmade works that carry an added layer of complexity and intellectual challenge.

In intaglio printmaking, the image is cut or etched into a metal plate, ink is worked into the incised lines, and the surface is wiped clean before the plate is run through a press. And, because the image must be carved in reverse to render correctly in the final print, the process requires great precision and attention to detail.

What prints is not the surface itself, but what lies beneath it. The artist commits to the image without seeing it fully until it is printed. This allows endless experimentation and nuances, making each print as distinctive and original as a single painting or watercolour.1

Sauvé, now 81, belongs to the post-1960s resurgence of graveurs (printmakers) in Québec, when artists reclaimed intaglio, etching, drypoint and aquatint as expressive, experimental media. He approaches landscape through poetic and process-driven exploration rather than narrative description.2

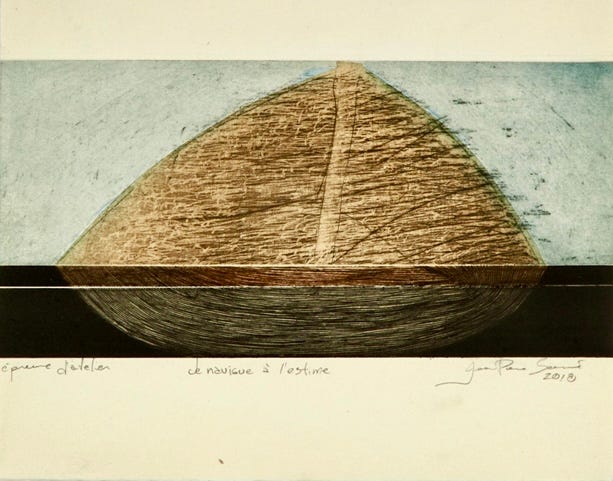

A l’estime is a French nautical term meaning navigation without precise instruments — relying on experience, judgment, and feeling. Sauvé’s piece above, Je navigue à l’estime, conveys the poetic sense of moving forward as interior, intuitive act, guided by perception and trust. The work suggests that creativity emerges in uncertainty—through attentiveness to what cannot be fully measured or known.

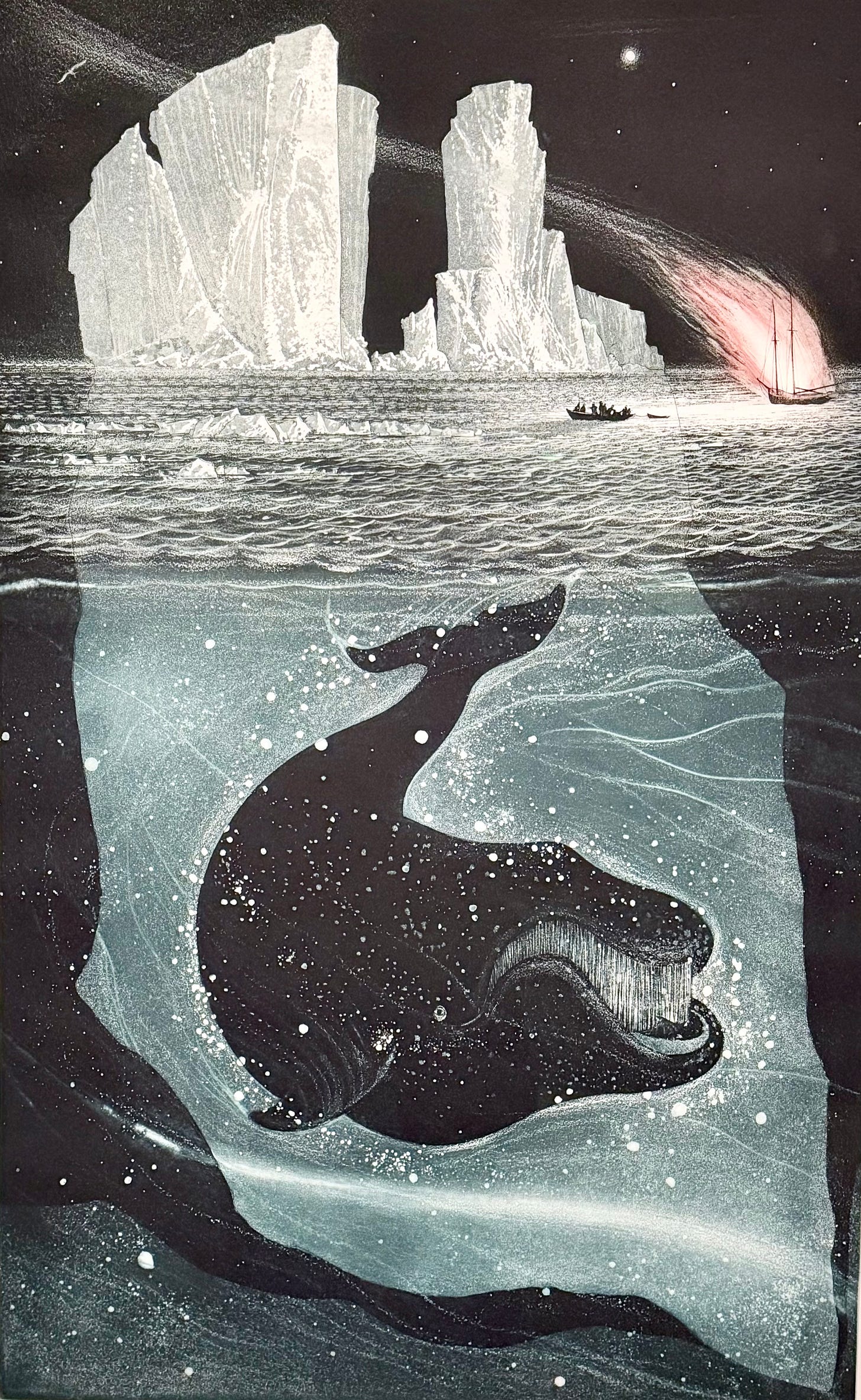

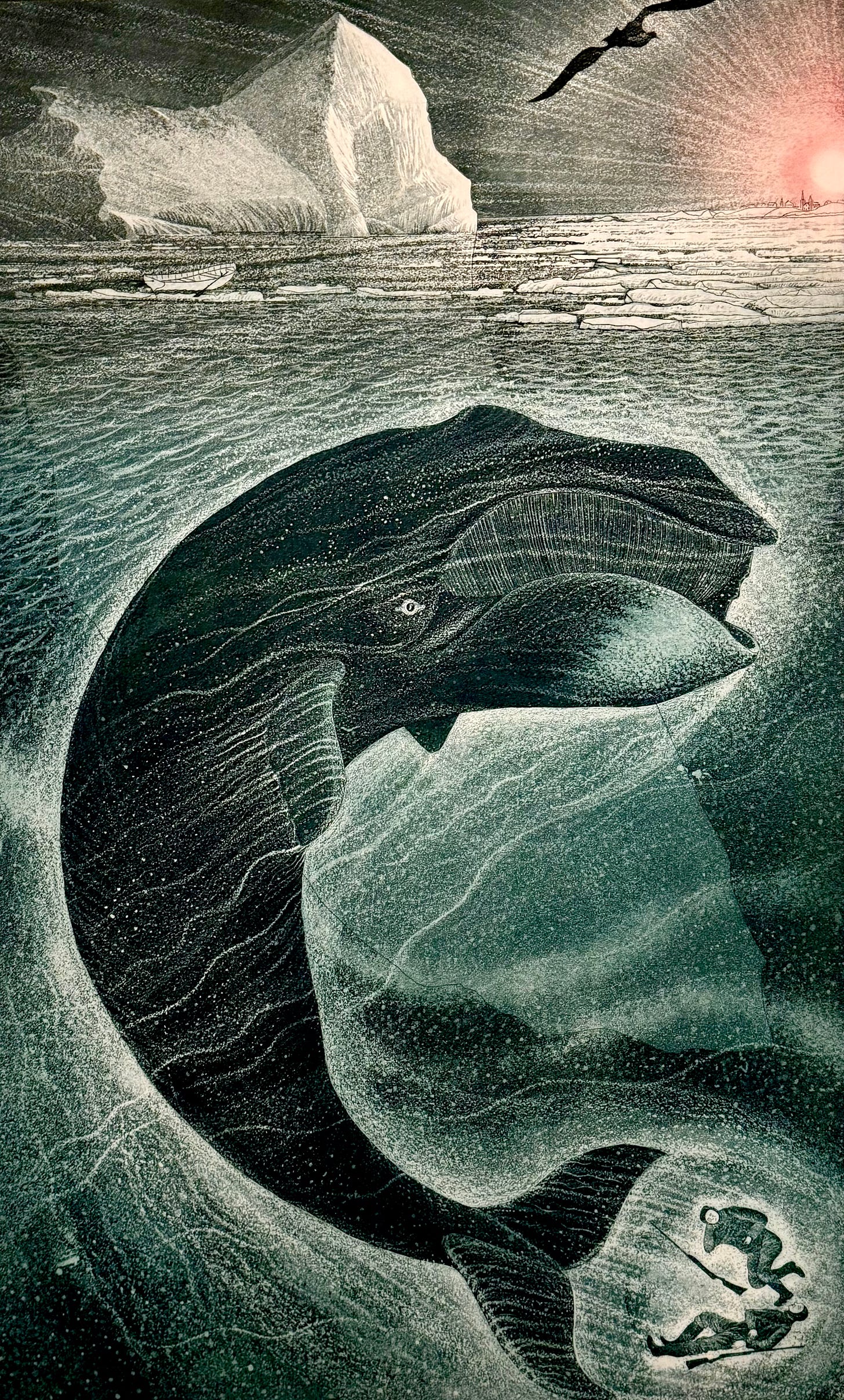

It was with this understanding—of printmaking as a medium rooted in layers, trust and the slow reveal—that I found myself last week at the Art Gallery of Ontario seeing a David Blackwood exhibit.

One of Canada’s best-known printmakers, Blackwood put onto paper an enduring vision of home. Born and raised on Bonavista Bay in Newfoundland, his hauntingly beautiful images—suffused with struggle and myth—are drawn from childhood memories, dreams, superstitions, legends, and oral traditions.

Images emerge from cold places and uncertain passages, shaped by lived experience, memory, and endurance. If Sauvé’s prints feel like acts of navigation and observation, Blackwood’s confront the peril and gravity of journeying head-on, reminding us that some landscapes—and some histories—are etched not only onto the copper printing plates, but but deep into the culture of a community.3

“At this point, we have no idea what lurks beneath the surface! Regardless, there is never disappointment.”

Note from David Blackwood to Juanita Wiersma, October 2014, his trusted printmaker, who assisted him with printing during a critical illness in the last decade of his life

As I learned at the exhibit, Blackwood famously used an iterative process for his printmaking, making incremental adjustments, adding colour, layering details, so that the latest print in a series was never guaranteed to be the last. As he aged and became ill, he found freedom in never reaching that end point. “I’m in a position where I feel free to destroy the thing if need be … so there’s a feeling of exploration, a wonderful feeling of knowing you still have something to discover, something to learn,” Blackwood said. “I’m terrified of formulaic work.”4

As Blackwood played with depth and velvety blackness giving way to shades of maritime blue and occasional reds, the profound sense of place he evoked for his recurring subjects—the ice, sea, and the isolated lives of mariners and outport communities of his native Newfoundland—gave his prints an atmospheric quality that underscore themes of time, danger, and solitude.5

Walker, there is no path,

the path is made by walking.—Campos de Castilla, Antonio Machado, Spanish poet

Perhaps it is no small coincidence that I first saw those beautiful whales in icy cold waters and encountered intaglio printing in 2022, a few weeks after David Blackwood’s death. While it would take me more than three years to discover Blackwood’s mastery, that introduction in a sleepy hamlet in Charlevoix via Jean-Pierre Sauvé was the first unearthing of the printmaker’s magic.

Like our meanderings in life, in intaglio printing, the end can’t be known until it is reached. It’s a beautiful analogy to the creative process itself—one that may take an intuitive turn for the better, if we only let our internal navigational tools guide us.

If you enjoy these Dispatches—and I hope you do—tap the heart, share, or comment to help new readers find their way here

Sardine rillettes

adapted from Around My French Table, Dorie Greenspan

Makes 1 cup or about 6 servings

To find the best sardines, you’ll have to swim across the Atlantic from Newfoundland to Portugal, where these nutrient-rich fish are in abundance. But no matter—excellent canned sardines from Portugal and elsewhere are readily found. Be sure to stock these in your cupboard to make this delicious snack any time the mood strikes.

Ingredients

2x 3¾-oz (106 gr each) cans sardines packed in olive oil and drained

2½ oz (70 gr) cream cheese

2 shallots, minced, rinsed, and patted dry

1–2 green onions, white and light green parts only, halved lengthwise and thinly sliced

Juice of 1 lime, or to taste

2–3 tablespoons minced fresh herbs, such as chives, cilantro, parsley, and/or dill

Pinch of piment d’Espelette or cayenne pepper

Salt and freshly ground pepper to taste

Put the cream cheese in a medium bowl and, using a rubber spatula, work it until it is smooth. Add everything else except the sardines—including a bit of some of the lime juice—until everything is blended

Break apart the sardines and add them to the bowl. Switching to a fork, mash and stir the sardines thoroughly into the mixture. The texture will not be entirely smooth. Taste for seasoning, adding more lime juice, salt, and/or pepper, if you’d like.

Scrape the rillettes into a bowl and cover, pressing a piece of plastic wrap against the surface. Chill for at least 2 hours, or for as long as overnight.

I'm working on a new brand and have been trying to learn more about printmaking — this is so informative and inspiring!!

I love this, Elizabeth! I haven't heard of Sauvé, but I saw Blackwood's work and it is breathtaking.